OUR HISTORY: AN OVERVIEW

By 1903, things had gotten out of hand. Philadelphia had become “the worst-governed city in America,” the muckraker Lincoln Steffens said in a magazine article titled “Philadelphia: Corrupt and Contented.”

Not everyone was content, and on Nov. 14, 1904, a group of business and civic leaders that included names still familiar today (Strawbridge, Fels) met at the Philadelphia Bourse to do something about it. Two months later, the Committee of Seventy was up and running.

It wasn’t the first time that civic elites concerned about corruption’s toll on their enterprises and the local economy had banded together to push for better government. Nor was it Philly’s first good-government group with a number in its name. There was the Citizens Committee of Fifty for a New Philadelphia (1890) and the Citizens Committee of Ninety-Five for Good Government (1895).

So why did we land on Seventy? It’s in the Bible, the books of Exodus and Numbers, specifically: God orders an overworked Moses to enlist the help of 70 “elders” in leading the Israelites to the Promised Land. It was a well-known reference in 1904, and we’ve kept the name because it represents a powerful brand with the politically engaged. Besides, who can argue with the idea of wise heads offering solutions to common problems? That’s what our 70-member Board of Directors has been doing ever since.

In 1904, the Republican machine had run City Hall for 46 years (with only one four-year hiatus in the 1880s), and wouldn’t relinquish it until 1952. The Democrats have held power ever since, so some things have yet to change. But we can point to many successes, beginning with convictions of ballot-box stuffers soon after we began monitoring elections in 1905. Here are some other 20th-century accomplishments for which we can take some credit…

- The creation of Philadelphia’s Municipal Court in 1913.

- The 1919 and 1951 Home Rule Charters. Among other things, the 1919 Charter required the mayor to present an annual city budget to City Council. Incidentally, the chairman of the commission that drew it up, publisher John C. Winston, was also Seventy’s first board chair.

- Reforms in the Civil Service Commission in the 1930s and ‘40s.

- Fairer alignments of state-legislative districts and city wards in the ‘60s.

We have also kept politicians from overreaching. In 1926, for instance, GOP boss William Vare stole a U.S. Senate election. Seventy squawked (as did Gov. Gifford Pinchot) and the Senate refused to seat Vare. And in the ‘70s, we shaped the debate in a nonpartisan campaign to defeat a proposed charter change that would have enabled Mayor Frank Rizzo to run for a third consecutive term.

And we have kept Philadelphians informed about their government. In the 1940s, we produced “Your Right to Vote,” a series of radio broadcasts. Our “Governance Project” began in 1979 (and led to the creation of the organization Pennsylvanians for Modern Courts). And in 1996, we began delivering our “News You Can Use” reports (one of the precursors to “How Philly Works”) via e-mail.

In this century, we have led the fight to defend campaign financing limits, established a city Board of Ethics and made lobbying (and the spending associated with it) a matter of public record. Our wars against pay-to-play politics and officeholder pension grabs helped to turn the ideas of better government and fair elections into a movement. And we continue to be the go-to organization for trustworthy background and analysis on issues related to Philadelphia’s political culture and its government. We have broadened our scope and expanded our mission in recent years, but we have never lost sight of why we were created in 1904: “To keep watch and ward over the public interests.”

Learn more on what we’ve done lately, or read on for the more detailed history below.

The Origin and Early Years of The Committee of Seventy

Republican Bosses and Machines

Seventy ’s Original Mission Statement

The Battle is Joined at the Polls

Seventy’s “City Party”

A Push for Honest Elections: 1920-1939

The Origin and Early Years of The Committee of Seventy

The Industrial Revolution, the Civil War, and large waves of immigration combined to turn William Penn’s “Greene Countrie Towne” into a sprawling city and manufacturing center. Robust and largely unregulated capitalism as well as rapid population growth resulted in a number of undesirable side effects including: overcrowded tenement housing, widespread poverty, dangerous working conditions, and the exploitation of child labor.

As the situation became more acute, a national reform movement started to grow among the working classes and some members of the urban elite who opposed the injustice and sought to remedy it as the abolitionists has successfully done a generation earlier. This movement, known as Progressivism, started in the late 1800’s and gave rise to the formation of the Committee of Seventy. The Industrial Revolution also facilitated the creation of the new middle class who rose to the forefront of Progressivism. The early Progressives were largely young, urban professionals who "sought to apply [the] principles of professions [such as medicine and law]" to alleviate societal ills.

One of Seventy’s precursors was the Citizen’s Municipal Reform Association (CMRA). Henry C. Lea, who was strongly supported by business leaders Wheeler, Baird, Drexel, and Lippincott, was largely responsible for the organization of the CMRA in June 1871 and the Reform Club in the spring of 1872. The CMRA was created in response to the establishment of the Public Buildings Commission by the state legislature in the summer of 1870. Citizens such as Reform publicist George Vickers feared that the government had created a body with unlimited tenure of office and that it had the ability to leisurely dole out taxes. Businessmen reformers, in particular, feared that because the city’s out of control finances would destroy their credit, and that the burden of taxation would destroy their future prosperity. The CMRA was concerned with arousing “public indignation” toward wrongdoing occurring within the Philadelphia government.

The 1880’s also marked the advent of Quayism, or the politically corrupt practice of using government through patronage to fund elections so that the state becomes accountable to Harrisburg , and not to the electorate. This model of government represented a severe blow to citizen participation. This is the context in which The Committee of Seventy operated when it first took up the cause of reform.

Moreover, the growth of the modern city and the simultaneous rise in immigration drastically changed the face of urban America ; the nature of tenement housing and ethnically segregated ghettos bred crime, disease, and poverty. Toward the end of the 19th Century a change in the ethnicity of immigrants also occurred. An increase in Southern European and Eastern European immigrants and the northern migration of African-Americans further diversified the political climate of Philadelphia at the turn of the century. Disfavored racial and ethnic groups were crowded into those areas of old housing and low paying industries.

The Progressive Movement arose in response to these changes in the form of many different organizations. The groups attacked and nationalized the issues of available education, racial discrimination, women's rights, child labor, and temperance. The CMRA and the Committee of Seventy made challenges on the governmental level, whereas the Citizens’ Committee of Fifty for a New Philadelphia (1890-1892) and the Citizen’s Committee of Ninety-Five for Good City Government (1895) worked to challenge the supremacy of the electoral arena. While the efforts of individual reformers (such as Jane Addams, the founder of the Hull House which aided the poor) and groups (such as the Women's Christian Temperance Union) made noteworthy advances during the heyday of Progressivism, The Committee of Seventy was Philadelphia’s only progressive era civic reform organization to maintain its cohesion and relevance throughout the 20th Century.

Republican Bosses and Machines

One of the main reasons that there was a need for Seventy was because the Republican bosses and machines had come to dominate Philadelphia government. It is important to first look at the Vare brothers. George, Edwin and William Vare had initially set up a small contracting business in South Philadelphia which quickly developed into a major street-cleaning operation. Between 1888 and 1921 they collected $18 million from fifty-eight street-cleaning contracts. In total, Vare interests received 341 public contracts worth more than $28 million. This profit gave the Vare brothers a chance to influence Philadelphia politics. For instance, William S. Vare and Joseph Klemmer donated their annual salaries of $10,000 and $5,000, as recorder of deeds and register of wills, respectively, to their organization’s coffers.

William Vare’s wealth allowed him to generate a lot of publicity and organize effective campaigns. “Service” became his personal slogan and in order to show the Organization’s readiness to accommodate the common citizen, its candidates promised everything and anything that would appeal to the populace. Whether it was better traffic conditions, a high school stadium, more efficient government, the return of the five-cent fare, and of course lower taxes, the Organization would promise it. These promises were made on a ward-by-ward basis, to further satisfy specific needs.

The Republican Organization’s control of city government was almost complete. For example, of the 254 bills reported favorably by the Organization in 1912, only 4 were rejected and 200 were passed unanimously. With the exception of a few defeats between 1905 and 1911, the Republican Party secured all city and county offices in Philadelphia between 1887 and 1933 (except where a statue required minority party representation). It was also not unusual for the Organization to prevail by landslides in local elections. For instance, in 1899, 1903, 1919 and 1923, mayoral candidates Ashbridge, Weaver, Moore, and Kendrick all were credited with well over 80 percent of the votes cast.

In addition, in 1905, the Republican Organization managed to not only win all of the judicial elections, but by shifting 55,000 voters over to the Democratic Party, the Organization also undermined the City Party’s effort to be the second party in Philadelphia. One of the Seventy’s early members, George W. Norris, had observed in 1915 that even the Democratic Party had become little more than a bi-partisan adjunct of the Republican Organization. They basically traded votes in return for a few salaried positions. William Vare, in fact, paid the rent on the Democratic Headquarters.

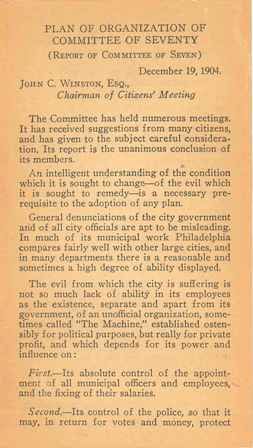

Seventy ’s Original Mission Statement

The longevity of Seventy is partially a product of its clearly stated and carefully reasoned goals. In order to pave the way for an organized and efficient organization, the Committee created a clear mission statement in 1904. The statement included four important goals:

1. Protect the ballot through vigorous enforcement of State election laws, and by working to improve the voting and registration process.

2. Work for the election of City officials devoted to the public interest, regardless of their political affiliations.

3. Aid honest city officials in the performance of their duties.

4. Gather and disseminate accurate, non-partisan information on municipal affairs.

It seems that Seventy’s goals were more a matter of rekindling civic concern and involvement in Philadelphia than a matter of legislative change or investigation and litigation.

There are several reasons why there was a need for the Committee of Seventy to form. By many accounts, Philadelphia was the worst-governed city in the United States at the turn of the century. The Republican Machine ruled politics and government. Public elections were routinely bought and sold. The fraud, graft, and political favoritism that riddled the City's government were publicized nationwide when muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens published his expose, " Philadelphia : Corrupt and Contented" in 1903. Existing civic organizations were unable to limit the corruption. In reaction to the deplorable condition of government which prevailed in Philadelphia , a group of business and community leaders formed the Committee of Seventy to fight for civic reform. Seventy was a product of a town meeting on November 14, 1904 that brought together the reform spirit of Philadelphia , to dramatically improve Philadelphia ’s political climate. The meeting, which was held in the Bourse building, was attended by many prominent Philadelphians, such as Calvert, Strawbridge and Fels. Also in attendance were members of the Municipal League, which was, at that time, one of Philadelphia ’s oldest reform organizations.

The Battle is Joined at the Polls

As its first priority, Seventy worked at the base of the situation to eliminate the blatant voter fraud that was prevalent in Philadelphia elections. In contrast to other reform groups that had experienced little success because they limited their efforts to public condemnation of the Republican Machine bosses. Seventy attacked the problem at its roots on the streets of Philadelphia.

In 1905, Seventy began to monitor the polls on Election Day and helped to prosecute individuals who violated the law. Seventy hired attorney Thomas Raeburn White, an expert on election law, and proceeded to collect evidence to ensure convictions. In 1906, Raeburn White testified in Harrisburg in support of ward realignment. Seventy enjoyed early success, having over one hundred elections officers and Republican ward leaders indicted on charges ranging from stuffing the ballot box to buying votes with shots of whiskey. As a result of the prosecutions, each of the ballot box stuffers who were convicted received 2 year sentences.

Similarly, before the Personal Registration Act of 1906, local newspapers and reformers estimated that the number of fraudulently registered voters in the city numbered between 30,000 and 80,000. These fraud votes consisted of forged signatures that included dead people, children and non-naturalized foreigners.

In 1909, Seventy's investigations revealed that 108 policemen had violated the Election Code by standing inside polling places and, in some instances, subjected poll workers to brutal assaults and unwarranted arrests. Many of these officers were later fired. By using the existing laws to clean up elections in Philadelphia, Seventy won citywide respect and forced the Republican Machine to develop new schemes for fixing the vote. In the 1911 election, the Committee investigated more than 1,500 alleged violations of the Shern Law and filed complaints against police officers and other city employees with the appropriate head of department. Despite these efforts, no action was ever taken against the offenders.

Seventy’s Election Day oversight was needed even more because of a giant increase in Philadelphia’s population. The city’s population had continued to grow in the 1920’s at approximately the same rate (20 percent) as it had in the early post-bellum period. This thus resulted in Philadelphia ’s population to rise from 1,000,000 in 1890 to almost 2,000,000 by 1930. In 1910, Seventy concluded an investigation regarding illegal voter assistance during the 1909 election. They also finished conducting an ongoing review of voter registration lists to strike invalid names. The Committee was able to get convictions and one year sentences for numerous violators. In addition to its efforts to clean up elections, Seventy also successfully advocated for the 1913 creation of the Philadelphia Municipal Court.

Furthermore, by 1916, the Committee had nearly 5,000 volunteers to monitor the city’s electoral processes, aided by the Committee’s offering rewards for information leading to the arrest of election law violators. The Committee also reinforced election-related legislation by sending warning letters to municipal officials. The Committee’s work was aided substantially by the inauguration of Mayor Blankenburg in 1911; Blankenburg proved much more responsive to the Committee’s agitation for reform than the previous mayor. Indeed, during Blankenburg’s term, 187 civil service employees were discharged for electoral law violations.

Perhaps one of the highlights of the Committee’s first 20 years was its first Charter reform in 1919; the chairman of the Charter Reform Committee was Seventy’s then-chairman, John C. Winston. The 1919 charter is widely considered Philadelphia ’s first “modern” charter and was created with the intention of correcting issues such as under-representation in certain districts, and the contracting of municipal services, such as garbage collection, to private companies. The 1919 Charter revised the city council system by decreasing membership, limiting terms, and restricting council members to that single municipal position. The charter also ensured that municipal services such as street maintenance, garbage collection, and city repairs were the responsibility of the city, and not to be assigned to individuals on contract. The punishment by fine or imprisonment for politically corrupt activities by city employees was formally documented, and municipal agencies were placed under the authority of the city’s controller and thus independent of mayoral control. The 1919 Charter also required the mayor to submit an annual budget to the City Council to be reviewed in public hearings, and instituted a Department of Social Welfare to aid individual citizens. In essence, the 1919 Charter was designed to eliminate many of the predominant methods of political corruption such as had been the focus of the Committee since its 1904 inception.

Seventy’s “City Party”

As a second strategy for civic reform, Seventy employed an unusual measure for a nonpartisan organization: it established and financed its own independent political party in 1905. The “City Party’s” formation played a major role in harnessing the reform insurgency that hit Philadelphia following Durham ’s proposal to lease the city’s gas works to UGI. Seventy's "City Party" financed and managed candidates in six elections and succeeded in electing reform-minded citizens to municipal office. Despite the success of this endeavor, Seventy disbanded the party after 1907, when it learned that such direct participation in electoral politics jeopardized its non-partisan status.

Seventy also sought to improve elections and government in Philadelphia by drafting and lobbying for reform legislation in Harrisburg (the City's laws were in the hands of State legislators until 1949). Seventy's efforts were instrumental in winning key election and civil service reforms, and in the creation of a municipal court for Philadelphia . After several years of lobbying for a revised form of government in Philadelphia , Seventy won a major victory with the passage of a new charter for the City in 1919. This charter incorporated many of Seventy's proposals for reform. The centralization of power in the hands of a much smaller City Council and the increase in the City's ability to operate its own public works was a step forward in tracking responsibility.

A Push for Honest Elections: 1920-1939

As an organization, the Committee of Seventy changed little in the 1920s. It attempted to strengthen its ties to other civic organizations in Philadelphia and chose to diversify its membership by including women.

Early in the 1920s, the Committee of Seventy began to expand its scope of interest to include City finances as part of its concern for good government. At first, Seventy reviewed public works contracts that the City granted to private businesses. For many years, Philadelphia taxpayers had paid exorbitant sums for the construction and management of second-rate public works, such as the trolley and subway systems. Much of the money went to line the pockets of Republican bosses and select businessmen. Acting as a fiscal watchdog, Seventy went public with its criticism of fraudulent contracts and excessive spending.

Although Seventy had some success reforming Philadelphia 's elections in the first part of the century, many problems remained. Seventy continued to monitor elections in the 1920s and 1930s, and it acted on complaints received during each election. Cases were prepared and presented to the District Attorney if sufficient evidence was available to pursue a conviction. Seventy’s investigation of the 1926 U.S. Senatorial contest ended with the ouster of the newly elected Republican boss William Vare on charges of voter fraud. The Senate refused to seat Vare because his family had a notorious reputation for fraudulent voter registration, purchase of votes from poor citizens, and ballot-box stuffing, among other illegal practices. After three years of investigation and delay Vare was still denied his seat in the U.S. Senate, due to the fact that he had spent too lavishly on the Republican primary. The public awareness of Vare Machine misconduct can be accounted to the efforts of the Committee.

Between 1925 and 1927, Seventy secured the convictions of approximately forty registrars and election officers on Election Code violations. Seventy also continued to push for long-term election reform through legislation. Because of the efforts of Seventy, the procedures for voter registration were tightened to discourage vote fraud through the misuse of registration binders.

As an extension of its concern for honest elections, Seventy launched a campaign in 1928 to have mechanical voting machines installed in every Philadelphia voting division. Seventy argued that the machines would standardize voting procedures across the city, and would eliminate some methods of falsifying election returns. Against the stiff opposition of the Republican-controlled County Commission, the agency in charge of elections, Seventy eventually prevailed. Although voting machines would not be installed city-wide until 1946, they were used in most wards in the 1930s.

In the 1930s, Seventy sued to stop the political manipulations of Mayor S. David Wilson with the City's Sinking Fund and gas works and even drew up plans by which the City could relieve its indebtedness. In the 1930s, Seventy also made an effort to recruit young citizens, recognizing that many of its members were elderly veterans of the reform movement. These new members worked as volunteers to collect and analyze data on numerous topics, and gave Seventy the ability to conduct its investigations at little expense. Seventy received some of its funding from foundation grants, but members continued to supply the majority of the funds for its operating budget. Moreover, near the end of the decade, Seventy also organized a War Time Round Table to discuss the issues surrounding WWII on the radio.